China ban on use and sale of tiger and rhino parts does not include captive-bred specimens

On Friday 13 May, EIA posted an alert on social media about China considering a comprehensive ban on the use and sale of tiger and rhino parts in relation to a public consultation on the Measures for the Management of the Special Marking System for National Key Protected Terrestrial Wild Animals and Products thereof by the National Forestry and Grassland Administration.

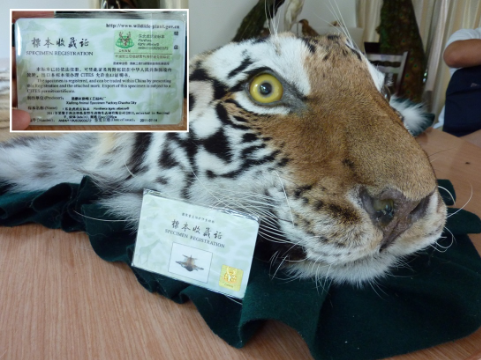

One of the documents stated that trade in tiger & rhino skins, taxidermy and other body parts, including those used in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) was prohibited under this marking scheme. However, it was not clear if the proposed measures would also apply to captive-bred specimens, which is another source of tiger products in China.

Tiger skin for sale in China ©EIA

EIA Wildlife Campaigner Veronika Spurna said: ‘At first we were encouraged to see this strong language, a reiteration of the ‘three strict bans’ announced in 2018. A truly impactful measure would mean explicitly banning the use of captive-bred tigers and rhinos.”

Chinese tiger facilities hold up to 6,000 specimens, which stands in stark contrast to its 7–55 tigers in the wild. The skins of captive-bred tigers are still traded under a permit system in China, stimulating demand for their body parts worldwide, while captive-bred tiger bone is used to make tiger bone wine.

As we dug deeper, it unfortunately became clear that the prohibitions referred to do not apply to captive-bred specimens. The Measures are an implementing regulation, which is subordinate to China’s Wildlife Protection Law (WPL), which allows captive breeding and trade in wildlife for special purposes (Articles 25, 26 and 27). It is also subordinate to the 2018 State Council Notification, which permits medicinal use of captive-bred tiger and rhinos.

The State Council Notification was put on hold following widespread domestic and international backlash and State Council Executive Deputy Secretary-General Ding Xuedong subsequently announced ‘three strict bans’ to limit trade in tiger and rhino parts, but it still did not include an unequivocal ban on captive-bred specimens.

Tiger ‘wine’ on sale in China (c) EIA

EIA Policy Analyst Taylor Tench said: ‘”Rhinos continue to suffer from relentless poaching pressure due to consumer demand for their horn. While it’s good to see the explicit inclusion of the ‘three strict bans’ reflected in the proposed Measures, unfortunately as long as the 2018 State Council Notice is in force, the very real risk remains that rhino horn sourced from captive-bred animals could be exploited for medicinal production in China and drive up demand.”

To definitively curb trade in endangered wildlife used in TCM, other highly trafficked species also need to be included, such as leopards, pangolins and elephants. Leopards are being driven close to extinction as their bone is a coveted ingredient in TCM and a common substitute for tiger parts. The majority of pangolins seized worldwide (71 per cent) are destined for China to be used for their scales in TCM. While China’s law enforcement agencies are uncompromising to wildlife smugglers, these efforts are undermined by parallel legal markets for some species that stimulate demand. There was also no mention about stopping the use of lion bone.

The proposed special marking system focuses on 12 parrot and seven reptile species, traded as exotic. Some of the parrot species proposed, such as parakeet (Psittacula krameri) and Monk (Myiopsitta monachus) are common species, but others such as the Grey parrot (Psittacus erithacus) are an endangered CITES Appendix I species. We are unsure what criteria were used to develop these lists since some of these are species where wild-caught specimens are illegally caught and falsely traded as ‘captive-bred’. The reptiles section contains the radiated tortoise among others, which is Critically Endangered.

Facilitating trade in the listed species is also a cause for concern because the accompanying explanatory note of the Measures further states that “the scope of special markings should be expanded as much as possible”, suggesting this is just the first list of species to be subject to this particular system, such as captive-bred tiger skins.

We will be watching closely for further developments, particularly as the revision of the Wildlife Protection Law draws near in October. For a real change to occur to the benefit of rhinos and tigers, the Law needs to remove all ambiguity surrounding the use of captive specimens and explicitly ban all trade, including through the repeal of the 2018 State Council Order.

Read our full response to the public consultation.